Convivial Home

Program: Co-living

Location: Seoul

Status: publication and exhibition - STUFF / NEXT HOME SEOUL

Year: 2017

design and concept: Ryszard Rychlicki

texts and contextualization: Karolina Ferenc

1. Example of typical apartment layout in Seoul

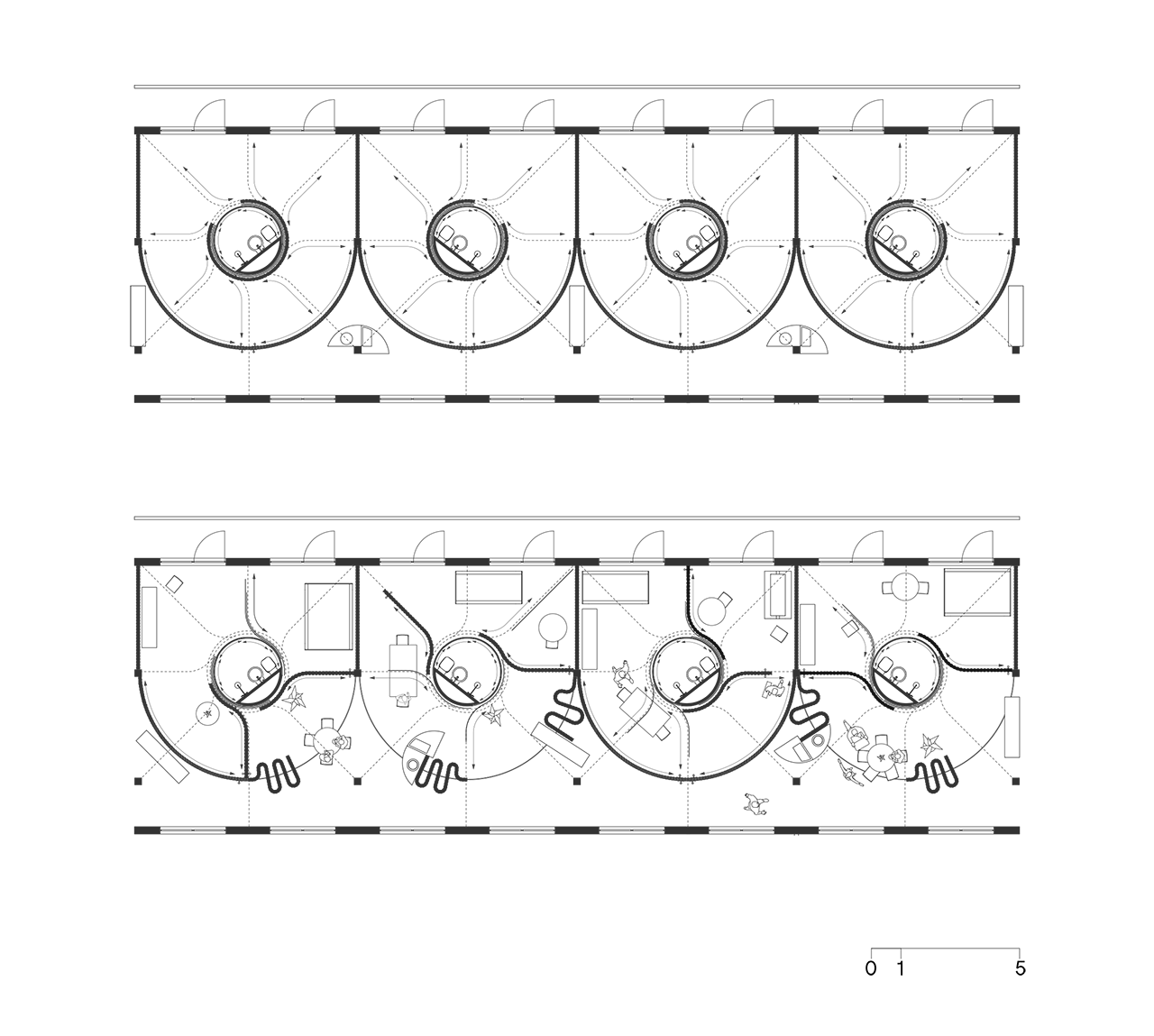

2. Blurred boundaries-adjustable program

3. Seoul, Sanggye-dong, extracted existing apartment layout

4. Existing layout typology modification

A - 50m2 floor

B - foldable wall

C - privacy layers (movable space dividers)

c1 - visual & acoustic layer

c2 - gradient screen - intimate visual barrier

c3 - functional mesh - work layer

D - central bathroom

E - ceiling rails

F - mobile kitchen

G - mobile storage

H - mobile/foldable bed

This project is a speculative rental-housing prototype involving a transgenerational co-living as an alternative to traditional mass housing apartments.

The key aspect of this project - a transgenerational co-living - can be described as a ground for a free exchange of a knowledge and support that might contribute to a self-sufficiency of people being in difficult living situation. The project follows the ethos of collective self-help and culture of sharing.

One of the major origin of current social issues in Korea is its quickly aging society. Between 1955-1960 and 1968-1974 South Korea experienced two baby booms. Number of baby boomers comprises 34 % of total population1. Together with a drastically low birth rate, baby boomers give an image of gradually aging population. Older generations dominate job market in South Korea, thus living very little work options for young people. In addition to joblessness, so-called Millennials have to face an upcoming higher taxes to cover retirement pensions of Baby Boom generation. This millennial generation is nicknamed ‘Give-up Generation’ referring to things that young people have been forced to give up on - dating, marriage, childbirth, steady (or even any) employment and home ownership.

According to OECD economic survey in 2016 South Korea noted the highest rate of elderly poverty(2). Half of Korea’s elderly- generation that helped to rebuild the economy after Korean war-are considered in poverty. About a quarter live alone. Many struggle with living in isolation and depression(3). Problem becomes even bigger in context of population aging - Korea’s population is rapidly becoming the world’s oldest according to The Lancet(4). Apart of late establishment of pension system (1988) and slowing economy, another reason of this situation is a shift in traditional Confucian values of filial piety. Many of seniors are not eligible for financial support because government records show that they have children, who are assumed to be taking care of them. In reality these elders don’t even have contact with their children. In the past caring for the elderly was considered as responsibility of the kids. “Over the past 15 years, the percentage of children who think they should look after their parents has shrunk from 90% to 37%, according to government polls”(5). Being separated from children together with being widowed and being divorced late in life are few of the reasons of increasing number of elderly single households which is mostly an involuntary situation that elderly find difficult to deal with economically as well as psychologically.

Housing problems applies as well to younger generations. One of the extreme example of dealing with housing issues related to renting prices is Goshiwon(6). It is a housing type occurring in South Korea since more than 40 years. Originally Goshiwon was a temporary and cheap accommodation for students, who spent most of their time preparing for exams. Usually it consists of a very tight room (less that 5 sqm) with a communal kitchen and bathroom. Sometimes one room can be shared with one more person. Due to house prices rise in Seoul, this form of housing became interesting not only for students but also for badly paid workers, mostly on the beginning or end of their professional carrier.

According to report commissioned by the Ministry of Health and Welfare in South Korea(7) aspects like income, residential environment, health level and housing type were worse in a single-person households than multi-person households. Moreover, percentage of poverty among people with jobs was 7,9% for multi-person households but 28,2% in case of single-person households. Apart from income issues there were also higher rates of chronic illness, signs of depression and suicidal thoughts.

All written above applied to a specific context of South Korea yet it is deeply related to more global struggles of nowadays societies.

1 - Kelsey Chong, South Korea’s Troubled Millennial Generation, April 27, 2016, Berkeley Haas

2 - OECD, Poverty rate66 year-olds or more, Ratio, 2015 Source: Income distribution

3 - Lam Shushan, Poor and on their own, South Korea’s elderly who will ‘work until they die’, 10 May 2017, Channel NewsAsia

4 - Penny Timms, South Koreans to live longest among developed nations by 2030, researchers project, 22 Feb 2017, The World Today, ABC News

5 - Chico Harlan for the Washington Post, South Korea’s rapid economic rise leaves many of its elderly facing poverty, 24 January 2014, The Guardian

6 - Jun Michael Park, Goshitel: Refuge for Those Who Can’t Help It, April 7, 2017, Korea Expose

7 - Hwangbo Yon, Single person households rise to most common form of household in South Korea, October 1, 2016, The Hankyoreh

The

only fully separated and fixed space within the unit is a shared bathroom. It

is separate because we consider it as the most intimate area within a shared

home. It is fixed because of a technical reasons. Privacy layer (movable space

dividers) are wrapped around the bathroom in the centre. Rest of the space can

be freely arranged with help of the space dividers into sleeping, dining,

cooking area and so on. 50m2 unit is intend for a mixed age group with a

special focus on students, young professionals, and elderly. Every unit can be

occupied with at least 2 people. Inhabitants need to decide on their own about

the arrangement of the space. The interior elements allow for a spontaneous

rearrangements of the unit program. 2 units are connected with each other by

the kitchen area. It’s up to inhabitants how they divide and arrange their

private and shared space or how many people they want to live with in total.

Relationship between objects that a typical living space contains and consists

of like walls, doors, corridors, or kitchen are fluid, and can be

adjusted/moved/replaced.

The

only fully separated and fixed space within the unit is a shared bathroom. It

is separate because we consider it as the most intimate area within a shared

home. It is fixed because of a technical reasons. Privacy layer (movable space

dividers) are wrapped around the bathroom in the centre. Rest of the space can

be freely arranged with help of the space dividers into sleeping, dining,

cooking area and so on. 50m2 unit is intend for a mixed age group with a

special focus on students, young professionals, and elderly. Every unit can be

occupied with at least 2 people. Inhabitants need to decide on their own about

the arrangement of the space. The interior elements allow for a spontaneous

rearrangements of the unit program. 2 units are connected with each other by

the kitchen area. It’s up to inhabitants how they divide and arrange their

private and shared space or how many people they want to live with in total.

Relationship between objects that a typical living space contains and consists

of like walls, doors, corridors, or kitchen are fluid, and can be

adjusted/moved/replaced.It is believed that collective living might be a way to foster interpersonal bonds and - consequently - fight a loneliness, isolation and inequality amongst students, young professionals and elderly. It may help younger inhabitants to feel more comfortable with the idea of getting older in a society obsessed with youth and restrained by same-age group education. As Ivan Illich argued1, education shouldn’t be limited to a specific age group in order to allow all people, despite their age, to learn from each other, the same might be applied to co-housing, where both - young and old - would benefit from living in diverse environment. Dealing together with both - routine and unexpectedness - of everyday life situations might offer a positive lesson from sociality and togetherness for those who suffer loneliness or frustration caused by extreme individualization in modernity.

The interior within this project becomes a tool for a spontaneous and active creation of living space, which is not only a space for sleeping and eating but, perhaps, for a support and caring as involvement and participation is needed to create and define the space. This new form of home unit aims to provide care and informal education - a place of production, not only consumption.